Memory Types

Memory Addresses and Hexadecimal Numbers

Understanding the number system used by computers to store and process data is essential for effective memory management, which is why we will start with an introduction into the binary and hexadecimal number systems and the structure of memory addresses.

Early attempts to invent an electronic computing device met with disappointing results as long as engineers and computer scientists tried to use the decimal system. One of the biggest problems was the low distinctiveness of the individual symbols in the presence of noise. A 'symbol' in our alphabet might be a letter in the range A-Z while in our decimal system it might be a number in the range 0-9. The more symbols there are, the harder it can be to differentiate between them, especially when there is electrical interference. After many years of research, an early pioneer in computing, John Atanasoff, proposed to use a coding system that expressed numbers as sequences of only two digits: one by the presence of a charge and one by the absence of a charge. This numbering system is called Base 2 or binary and it is represented by the digits 0 and 1 (called 'bit') instead of 0-9 as with the decimal system. Differentiating between only two symbols, especially at high frequencies, was much easier and more robust than with 10 digits. In a way, the ones and zeros of the binary system can be compared to Morse Code, which is also a very robust way to transmit information in the presence of much interference. This was one of the primary reasons why the binary system quickly became the standard for computing.

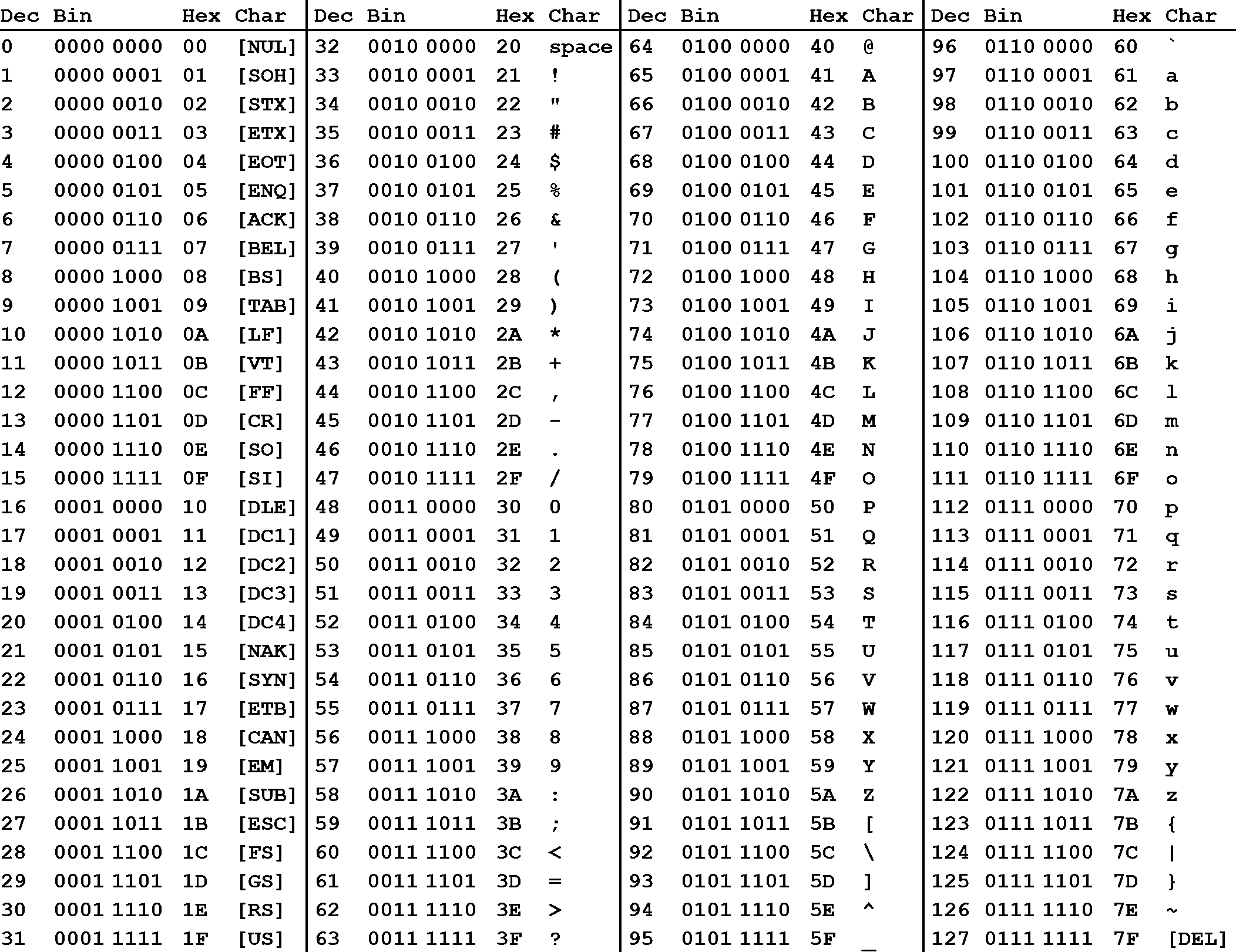

Inside each computer, all numbers, characters, commands and every imaginable type of information are represented in binary form. Over the years, many coding schemes and techniques were invented to manipulate these 0s and 1s effectively. One of the most widely used schemes is called ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange), which lists the binary code for a set of 127 characters. The idea was to represent each letter with a sequence of binary numbers so that storing texts in computer memory and on hard (or floppy) disks would be possible.

The film enthusiasts among you might know the scene in the hit movie "The Martian" with Mat Daemon, in which an ASCII table plays an important role in the rescue from Mars.

The following figure shows an ASCII table, where each character (rightmost column) is associated with an 8-digit binary number:

In addition to the decimal number (column "Dec") and the binary number, the ASCII table provides a third number for each character (column "Hex"). According to the table above, the letter z is referenced by the decimal number 122, by the binary number 0111 1010 and by 7A. You have probably seen this type of notation before, which is called "hexadecimal". Hexadecimal (hex) numbers are used often in computer systems, e.g for displaying memory readouts - which is why we will look into this topic a little bit deeper. Instead of having a base of 2 (such as binary numbers) or a base of 10 (such as our conventional decimal numbers), hex numbers have a base of 16. The conversion between the different numbering systems is a straightforward operation and can be easily performed with any scientific calculator. More details on how to do this can e.g. be found here.

There are several reasons why it is preferable to use hex numbers instead of binary numbers (which computers store at the lowest level), three of which are given below:

-

Readability: It is significantly easier for a human to understand hex numbers as they resemble the decimal numbers we are used to. It is simply not intuitive to look at binary numbers and decide how big they are and how they relate to another binary number.

-

Information density: A hex number with two digits can express any number from 0 to 255 (because 16^2 is 256). To do the same in the binary system, we would require 8 digits. This difference is even more pronounced as numbers get larger and thus harder to deal with.

-

Conversion into bytes: Bytes are units of information consisting of 8 bits. Almost all computers are byte-addressed, meaning all memory is referenced by byte, instead of by bit. Therefore, using a counting system that can easily convert into bytes is an important requirement. We will shortly see why grouping bits into a byte plays a central role in understanding how computer memory works.

The reason why early computer scientists have decided to not use decimal numbers can also be seen in the figure below. In these days (before pocket calculators were widely available), programers had to interpret computer output in their head on a regular basis. For them, it was much easier and quicker to look at and interpret 7E instead of 0111 1110. Ideally, they would have used the decimal system, but the conversion between base 2 and base 10 is much harder than between base 2 and base 16. Note in the figure that the decimal system's digit transitions never match those of the binary system. With the hexadecimal system, which is based on a multiple of 2, digit transitions match up each time, thus making it much easier to convert quickly between these numbering systems.

Each dot represents an increase in the number of digits required to express a number in different number systems. For base 2, this happens at 2, 4, 8, 32, 64, 128 and 256. The red dots indicate positions where several numbering systems align. Note that there are breaks in the number line to conserve space.

Types of Computer Memory

Below you will find a small list of some common memory types that you will surely have heard of:

-

RAM / ROM

-

Cache (L1, L2)

-

Registers

-

Virtual Memory

-

Hard Disks, USB drives

Let us look into these types more deeply: When the CPU of a computer needs to access memory, it wants to do this with minimal latency. Also, as large amounts of information need to be processed, the available memory should be sufficiently large with regard to the tasks we want to accomplish.

Regrettably though, low latency and large memory are not compatible with each other (at least not at a reasonable price). In practice, the decision for low latency usually results in a reduction of the available storage capacity (and vice versa). This is the reason why a computer has multiple memory types that are arranged hierarchically. The following pyramid illustrates the principle:

Computer memory latency and size hierarchy.

As you can see, the CPU and its ultra-fast (but small) registers used for short-term data storage reside at the top of the pyramid. Below are Cache and RAM, which belong to the category of temporary memory which quickly loses its content once power is cut off. Finally, there are permanent storage devices such as the ROM, hard drives as well as removable drives such as USB sticks.

Let us take a look at a typical computer usage scenario to see how the different types of memory are used:

-

After switching on the computer, it loads data from its read-only memory (ROM) and performs a power-on self-test (POST) to ensure that all major components are working properly. Additionally, the computer memory controller checks all of the memory addresses with a simple read/write operation to ensure that memory is functioning correctly.

-

After performing the self-test, the computer loads the basic input/output system (BIOS) from ROM. The major task of the BIOS is to make the computer functional by providing basic information about such things as storage devices, boot sequence, security or auto device recognition capability.

-

The process of activating a more complex system on a simple system is called "bootstrapping": It is a solution for the chicken-egg-problem of starting a software-driven system by itself using software. During bootstrapping, the computer loads the operating system (OS) from the hard drive into random access memory (RAM). RAM is considered "random access" because any memory cell can be accessed directly by intersecting the respective row and column in the matrix-like memory layout. For performance reasons, many parts of the OS are kept in RAM as long as the computer is powered on.

-

When an application is started, it is loaded into RAM. However, several application components are only loaded into RAM on demand to preserve memory. Files that are opened during runtime are also loaded into RAM. When a file is saved, it is written to the specified storage device. After closing the application, it is deleted from RAM.

This simple usage scenario shows the central importance of the RAM. Every time data is loaded or a file is opened, it is placed into this temporary storage area - but what about the other memory types above the RAM layer in the pyramid?

To maximize CPU performance, fast access to large amounts of data is critical. If the CPU cannot get the data it needs, it stops and waits for data availability. Thus, when designing new memory chips, engineers must adapt to the speed of the available CPUs. The problem they are facing is that memory which is able to keep up with modern CPUs running at several GHz is extremely expensive. To combat this, computer designers have created the memory tier system which has already been shown in the pyramid diagram above. The solution is to use expensive memory in small quantities and then back it up using larger quantities of less expensive memory.

The cheapest form of memory available today is the hard disk. It provides large quantities of inexpensive and permanent storage. The problem of a hard disk is its comparatively low speed - even though access times with modern solid state disks (SSD) have decreased significantly compared to older magnetic-disc models.

The next hierarchical level above hard disks or other external storage devices is the RAM. We will not discuss in detail how it works but only take a look at some key performance metrics of the CPU at this point, which place certain performance expectations on the RAM and its designers:

-

The bit size of the CPU decides how many bytes of data it can access in RAM memory at the same time. A 16-bit CPU can access 2 bytes (with each byte consisting of 8 bit) while a 64-bit CPU can access 8 bytes at a time.

-

The processing speed of the CPU is measured in Gigahertz or Megahertz and denotes the number of operations it can perform in one second.

From processing speed and bit size, the data rate required to keep the CPU busy can easily be computed by multiplying bit size with processing speed. With modern CPUs and ever-increasing speeds, the available RAM in the market will not be fast enough to match the CPU data rate requirements.

Cache Memory

Cache Levels

Cache memory is much faster but also significantly smaller than standard RAM. It holds the data that will (or might) be used by the CPU more often. In the memory hierarchy we have seen in the last section, the cache plays an intermediary role between fast CPU and slow RAM and hard disk. The figure below gives a rough overview of a typical system architecture:

System architecture diagram showing caches, ALU (arithmetic logic unit), main memory, and the buses connected each component.

The central CPU chip is connected to the outside world by a number of buses. There is a cache bus, which leads to a block denoted as L2 cache, and there is a system bus as well as a memory bus that leads to the computer main memory. The latter holds the comparatively large RAM while the L2 cache as well as the L1 cache are very small with the latter also being a part of the CPU itself.

The concept of L1 and L2 (and even L3) cache is further illustrated by the following figure, which shows a multi-core CPU and its interplay with L1, L2 and L3 caches:

L1, L2, and L3 cache

-

Level 1 cache is the fastest and smallest memory type in the cache hierarchy. In most systems, the L1 cache is not very large. Mostly it is in the range of 16 to 64 kBytes, where the memory areas for instructions and data are separated from each other (L1i and L1d, where "i" stands for "instruction" and "d" stands for "data". Also see "Harvard architecture" for further reference). The importance of the L1 cache grows with increasing speed of the CPU. In the L1 cache, the most frequently required instructions and data are buffered so that as few accesses as possible to the slow main memory are required. This cache avoids delays in data transmission and helps to make optimum use of the CPU's capacity.

-

Level 2 cache is located close to the CPU and has a direct connection to it. The information exchange between L2 cache and CPU is managed by the L2 controller on the computer main board. The size of the L2 cache is usually at or below 2 megabytes. On modern multi-core processors, the L2 cache is often located within the CPU itself. The choice between a processor with more clock speed or a larger L2 cache can be answered as follows: With a higher clock speed, individual programs run faster, especially those with high computing requirements. As soon as several programs run simultaneously, a larger cache is advantageous. Usually normal desktop computers with a processor that has a large cache are better served than with a processor that has a high clock rate.

-

Level 3 cache is shared among all cores of a multicore processor. With the L3 cache, the cache coherence protocol of multicore processors can work much faster. This protocol compares the caches of all cores to maintain data consistency so that all processors have access to the same data at the same time. The L3 cache therefore has less the function of a cache, but is intended to simplify and accelerate the cache coherence protocol and the data exchange between the cores.

Temporal and Spatial Locality

The following table presents a rough overview of the latency of various memory access operations. Even though these numbers will differ significantly between systems, the order of magnitude between the different memory types is noteworthy. While L1 access operations are close to the speed of a photon traveling at light speed for a distance of 1 foot, the latency of L2 access is roughly one order of magnitude slower already while access to main memory is two orders of magnitude slower.

Originally from Peter Norvig: http://norvig.com/21-days.html#answers

In algorithm design, programmers can exploit two principles to increase runtime performance:

-

Temporal locality means that address ranges that are accessed are likely to be used again in the near future. In the course of time, the same memory address is accessed relatively frequently (e.g. in a loop). This property can be used at all levels of the memory hierarchy to keep memory areas accessible as quickly as possible.

-

Spatial locality means that after an access to an address range, the next access to an address in the immediate vicinity is highly probable (e.g. in arrays). In the course of time, memory addresses that are very close to each other are accessed again multiple times. This can be exploited by moving the adjacent address areas upwards into the next hierarchy level during a memory access.

Virtual Memory

Problems with physical memory

Virtual memory is a very useful concept in computer architecture because it helps with making your software work well given the configuration of the respective hardware on the computer it is running on.

The idea of virtual memory stems back from a (not so long ago) time, when the random access memory (RAM) of most computers was severely limited. Programers needed to treat memory as a precious resource and use it most efficiently. Also, they wanted to be able to run programs even if there was not enough RAM available. At the time of writing (August 2019), the amount of RAM is no longer a large concern for most computers and programs usually have enough memory available to them. But in some cases, for example when trying to do video editing or when running multiple large programs at the same time, the RAM memory can be exhausted. In such a case, the computer can slow down drastically.

There are several other memory-related problems, that programmers need to know about:

-

Holes in address space : If several programs are started one after the other and then shortly afterwards some of these are terminated again, it must be ensured that the freed-up space in between the remaining programs does not remain unused. If memory becomes too fragmented, it might not be possible to allocate a large block of memory due to a large-enough free contiguous block not being available any more.

-

Programs writing over each other : If several programs are allowed to access the same memory address, they will overwrite each others' data at this location. In some cases, this might even lead to one program reading sensitive information (e.g. bank account info) that was written by another program. This problem is of particular concern when writing concurrent programs which run several threads at the same time.

The basic idea of virtual memory is to separate the addresses a program may use from the addresses in physical computer memory. By using a mapping function, an access to (virtual) program memory can be redirected to a real address which is guaranteed to be protected from other programs.

Expanding the available memory

What would happen if the available physical memory was below the upper bound imposed by the architecture? The following figure illustrates the problem for such a case:

In the image above, the available physical memory is less than the upper bound provided by the 32-bit address space.

On a typical architecture such as MIPS ("Microprocessor without interlocked pipeline stages"), each program is promised to have access to an address space ranging from 0x00000000 up to 0xFFFFFFFF. If however, the available physical memory is only 1GB in size, a 1-on-1 mapping would lead to undefined behavior as soon as the 30-bit RAM address space was exceeded.

With virtual memory however, a mapping is performed between the virtual address space a program sees and the physical addresses of various storage devices such as the RAM but also the hard disk. Mapping makes it possible for the operating system to use physical memory for the parts of a process that are currently being used and back up the rest of the virtual memory to a secondary storage location such as the hard disk. With virtual memory, the size of RAM is not the limit anymore as the system hard disk can be used to store information as well.

The following figure illustrates the principle:

With virtual memory, the RAM acts as a cache for the virtual memory space which resides on secondary storage devices. On Windows systems, the file pagefile.sys is such a virtual memory container of varying size. To speed up your system, it makes sense to adjust the system settings in a way that this file is stored on an SSD instead of a slow magnetic hard drive, thus reducing the latency. On a Mac, swap files are stored in/private/var/vm/.

In a nutshell, virtual memory guarantees us a fixed-size address space which is largely independent of the system configuration. Also, the OS guarantees that the virtual address spaces of different programs do not interfere with each other.

The task of mapping addresses and of providing each program with its own virtual address space is performed entirely by the operating system, so from a programmer’s perspective, we usually don’t have to bother much about memory that is being used by other processes.

Before we take a closer look at an example though, let us define two important terms which are often used in the context of caches and virtual memory:

-

A memory page is a number of directly successive memory locations in virtual memory defined by the computer architecture and by the operating system. The computer memory is divided into memory pages of equal size. The use of memory pages enables the operating system to perform virtual memory management. The entire working memory is divided into tiles and each address in this computer architecture is interpreted by the Memory Management Unit (MMU) as a logical address and converted into a physical address.

-

A memory frame is mostly identical to the concept of a memory page with the key difference being its location in the physical main memory instead of the virtual memory.

The following diagram shows two running processes and a collection of memory pages and frames:

As can be seen, both processes have their own virtual memory space. Some of the pages are mapped to frames in the physical memory and some are not. If process 1 needs to use memory in the memory page that starts at address 0x1000, a page fault will occur if the required data is not there. The memory page will then be mapped to a vacant memory frame in physical memory. Also, note that the virtual memory addresses are not the same as the physical addresses. The first memory page of process 1, which starts at the virtual address 0x0000, is mapped to a memory frame that starts at the physical address 0x2000.

In summary, virtual memory management is performed by the operating system and programmers do usually not interfere with this process. The major benefit is a unique perspective on a chunk of memory for each program that is only limited in its size by the architecture of the system (32 bit, 64 bit) and by the available physical memory, including the hard disk.